Welcome to the second issue of the first-ever newsletter dedicated to American futurist Patrick Gunkel. For at least the next year, this will be a weekly newsletter. How do I know? Because I’ve already written the first 25 issues and have working drafts of the remaining 27.

You might be wondering why you’re getting this newsletter.

If you are, it’s because we’ve corresponded about Gunkel in the past, or maybe you’re just a friend who got added. If you don’t want to learn more about Patrick Gunkel, it’s easy—just unsubscribe.

But before you decide to unsubscribe, you really have to ask yourself—why wouldn’t you want to learn more about Patrick Gunkel?

Why wouldn’t you want to learn more about one of the maddest unknown geniuses of the 20th century, the man who invented a whole new science that he called ideonomy (IDEA-onomy)?

Why wouldn’t you want to be one of the first people in the know?

Because I’m going to make certain, you see, that before this decade is out, the name Patrick Gunkel sits just a bit shy of Household Word.

Maybe you need to learn a bit more about me first, and why I’m doing this?

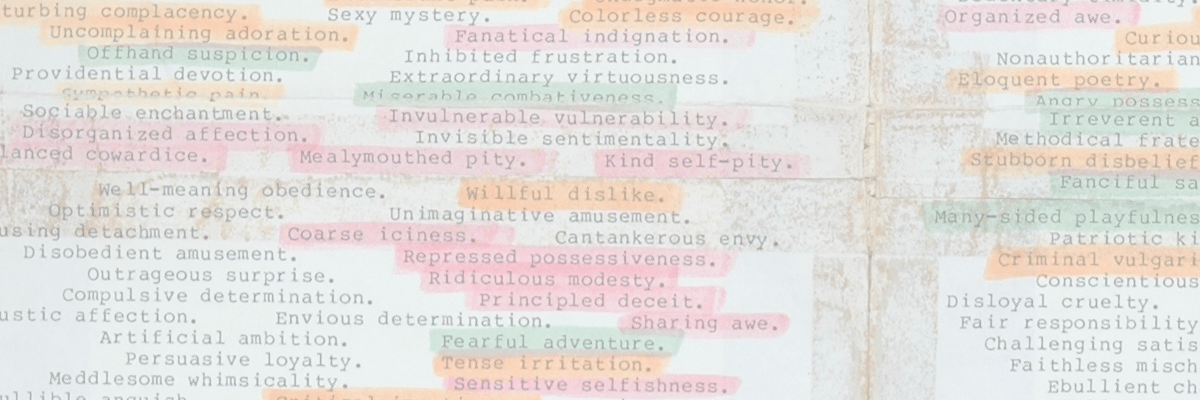

Well that might be interesting, but what I’d rather do is instead show you this copy of a list that 23-year-old Patrick Gunkel sent to MIT computer scientist Edward Fredkin in early 1971.

“Some of the Things Which I Want to Do Include…”

At the time Gunkel sent this list to Fredkin, he’d recently barged in on Fredkin and another well-known MIT computer scientist named Marvin Minsky on the MIT campus at the precise moment they were talking about unknown geniuses.

As the story goes, Fredkin was sitting in Minsky’s office one day in December 1970 when suddenly the 23-year-old Gunkel knocked fiercely on the door, invited himself in, and started saying so much brilliant stuff that Minsky decided to hire Gunkel on the spot despite the fact that Gunkel never graduated high school.1

It then fell to Fredkin to figure out how to get Gunkel onboard Project MAC, the famous MIT computer time-sharing experiment that was originally funded by U.S. intelligence agencies.

So Fredkin did what was normal in this situation—he asked Gunkel to send him a sort of statement of ambition, a prospectus outlining Gunkel’s career path for the future.

The list Gunkel sent Fredkin was anything but normal.2

I’ve included a photo of the full 14-point list below, but here’s the first four entries so you get the idea:

SOME OF THE THINGS WHICH I WANT TO DO INCLUDE:

1. See if it is not possible to put into my head a ‘complete’ picture of all of science, knowledge of the world, the universe of possibilities, society, the universe of possible alternative worlds, psychology, values, obligations, the structure of the mind, the structure of possibility, the present, the past, the future.

2. Actually transform all of the world, physically redirect it towards sane & noble goals; elevate the population, glorify the physical setting, scientifically structure society, orient the present to the preeminent future, advance understanding of fundamentals.

3. See whether a “true” sociology—rigorous, comprehensive, certain, predictive, controlling, choice-control-infinite, mechanistic, etc—is not possible of my or eventual creation.

4. See whether epistemology & physics & eschatology are not—now or eventually—reducible to some ultimate form & finite language

etc…

I’m tempted to let the letter speak for itself.

Who am I to tell you how to interpret something as far-out-there as this?

But no matter what you may think, I do want to flag something important about Gunkel, which is that no matter how crazy his writing might seem, and although his proposal is most certainly impossible for a person to actually achieve, the career goals Gunkel set out for himself at the age of 23 were nevertheless fairly logical.

Insanely, ridiculously, utterly over-ambitious, yes—but insane, illogical… no. Not at all.

And that, in my mind, is one of the central reasons why intellectuals like Fredkin, Minsky, and others, were drawn to Gunkel like moths to the flame.

Because Gunkel’s vision was absurdly vast, dressed up with big words and long lists, and yet still comprehensible.

It was not word salad, but neither was it grounded in any of the traditional vehicles of humanity or, for that matter, an elite computer science department like MIT.

Gunkel wasn’t saying he was going to change the world by becoming the President of the United States or change sports by becoming the Greatest Baseball Player in History.

He was a lateral thinker.

Even at the tender age of 23, Gunkel was dead-set on changing our view of reality rather than changing some smaller element within it.

Well… Did It Work?

The letter did work, sort of.

Gunkel was hired by MIT and worked for Fredkin under the umbrella of Project MAC for around 2.5 years.

However, in a strange turn-about that was typical of Gunkel, he didn’t do the logical thing and study artificial intelligence with his two would-be mentors.

Instead, he decided to become a neuroscientist and study the human brain.

Gunkel’s time at MIT was one of the high points of his life.

He even called himself an “MIT neuroscientist” for the rest of his life, even though he received no degree at MIT and the work he did was never reviewed or analyzed by anyone else in the field. (Gunkel’s brain manuscript still hasn’t been appropriately studied, hint hint.)

Although we are still some ways off from creating a science of ideas, I believe and will continue to advocate for the recognition that Gunkel—in his difficult, confusing way—truly invented something important.

So please don’t unsubscribe just yet.

Please stick around for the journey.

Because as someone who’s studied ideonomy for nearly ten years and intensively researched Gunkel for over three, I’ve got a pretty good sense of where we’re headed.

And trust me… it’s not just going to blow your mind, but reconfigure your reality.

Note: I have the right to disseminate this material. It may not be copied, stored, reproduced, or disseminated without express written permission. However, excerpts can and should be used for scholarly purposes.

References:

(1) “As the story goes….“ see: https://ideonomy.mit.edu/gunkel.html

(2) “The list Gunkel sent Fredkin…” Author’s original archival research. Author has the right to disseminate this material. It may not be copied, stored, reproduced, or disseminated without express written permission. However, excerpts can and should be used for scholarly purposes.